The Devil & Mr. Casement

Conclusive proof of forgery

Among the diaries attributed to Roger Casement there is a cash ledger for 1911 which is also part diary. This has been scrutinised by several authors, most closely by Jeffrey Dudgeon, the Belfast researcher who is today the leading forgery denier.

In 2002 Dudgeon published the first edition of his book bearing the title Roger Casement: The Black Diaries – with a study of his background, sexuality and Irish political life. This substantial volume purported to add rich detail and colour to the already widely established view that the diaries were authentic. Dudgeon was able to present much information about the north of Ireland in relation to Casement and also to provide something missing from other studies – what it was like to be an active homosexual in the North (and elsewhere) a hundred years ago. Dudgeon’s history recipe freely mixes fact with speculation and ‘in-the-know’ innuendo to promote his desired conclusions of authenticity which are guided more by an obvious bias than by impartial analysis. His book although stylistically challenging and idiosyncratic has gathered both attention and praise.

Dudgeon has never doubted the diaries are genuine and he no doubt believes he has demonstrated their authenticity to the highest degree possible. As the years passed his reputation grew as a veteran crusader who knew ‘the inside story’ and he became an influential expert consulted by authors, academics, journalists, guest speaking at conferences and appearing on the media. Such a success story that by the centenary year of 2016, he produced a second edition to meet steady demand. Then, only two years later in early 2019, he produced a third edition. There was however one small difference in this third edition. A certain sentence on page 285/6 had disappeared. The 27 word sentence, apparently insignificant, had been in print for 17 years but was deleted in 2019. To discover the motive for this unexplained deletion is also to discover its significance for the entire controversy about the diaries. The devil is in the detail we are told so let us look at the detail to find the devil.

The detail concerns an alleged affair between Casement and a young Belfast bank clerk called Millar; Casement did indeed know Millar and his mother through shared friends and acquaintances in Antrim but they had little in common politically. Readers of Anatomy of a lie will recall that the widely-believed story fabricated by MI5 agent Major Frank Hall and promoted by Dudgeon is logically demonstrated to be manufactured evidence. The purported affair features in the 1910 diary and in the 1911 ledger with events located in Belfast and environs. The story also involves a motorcycle owned by Millar in 1911 which vehicle was identified by Hall in 1915 along with the full name of its owner Joseph Millar Gordon. Hall passed this information to the cabinet meeting on 2nd August 1916 to overcome lingering doubts about the expediency of an execution next morning. Hall’s tactic succeeded.

§

In the ledger the following appears dated 3 June:

‘Cyril Corbally and his motor bike for Millar £25.0.0’.

Cyril Corbally was a noted croquet player from County Dublin who in 1910 worked at Bishop’s Storton Golf Club in Essex. In 1910 he acquired a second hand Triumph motor cycle registered with Essex County Council. In 1911 Corbally sold the machine and in July Millar registered ownership with the same Council.

The sentence is understood to mean that the diarist is paying £25 to Corbally to purchase his motorcycle for Millar. Research has confirmed that £25 is a realistic price in 1911 for a three-year-old Triumph motorcycle; a new machine in 1908 cost around £50. However, as a simple record of a purchase the sentence is suspect because it contains four items of information when two would have been sufficient. It was not necessary to record the vendor’s name, the item bought, the purpose of the transaction and the sum paid. The vendor’s name and the price would have been enough to record the purchase. The extra information -purpose and item bought – is superfluous unless intended for third parties who the diarist knows will read the ledger. In short, the sentence is an artifice.

There are two further references to the alleged transaction in the ledger; on June 8 which reads ‘Carriage of motorbike to dear Millar. 18/3’ and at the end of June ‘Epitome of June A/C Present etc. to others Cyril Corbally…25.0.0.’ Outside the ledger there is no evidence that Casement ever contacted Corbally; nor is there any reference to the purchase of a motorcycle.

§

Here is the sentence which Dudgeon deleted from his third edition of 2019. ‘It is possible that Millar bought the motor bike from Corbally and that Casement was repaying him as a separate note* (see below) listing expenditure simply reads “Millar 25.0.0”.’

This sentence published by Dudgeon from 2002 to 2019 fatally compromises his overall endeavour to persuade us of authenticity. It signifies serious confusion; he does not know who paid for Millar’s motorcycle. It also signifies that he admits the possibility that Casement did not pay Corbally as alleged in the ledger which therefore would be a forgery. This confusion signals that Dudgeon is unable to make sense of the ledger and consequently has lost faith in his project. He cannot explain why if Millar paid Corbally, the ledger records that Casement also paid Corbally. It is possible that an astute, well-meaning reader alerted Dudgeon to the fatal implications of that sentence but after 17 years it seems improbable that he suddenly discovered the gaffe by himself.

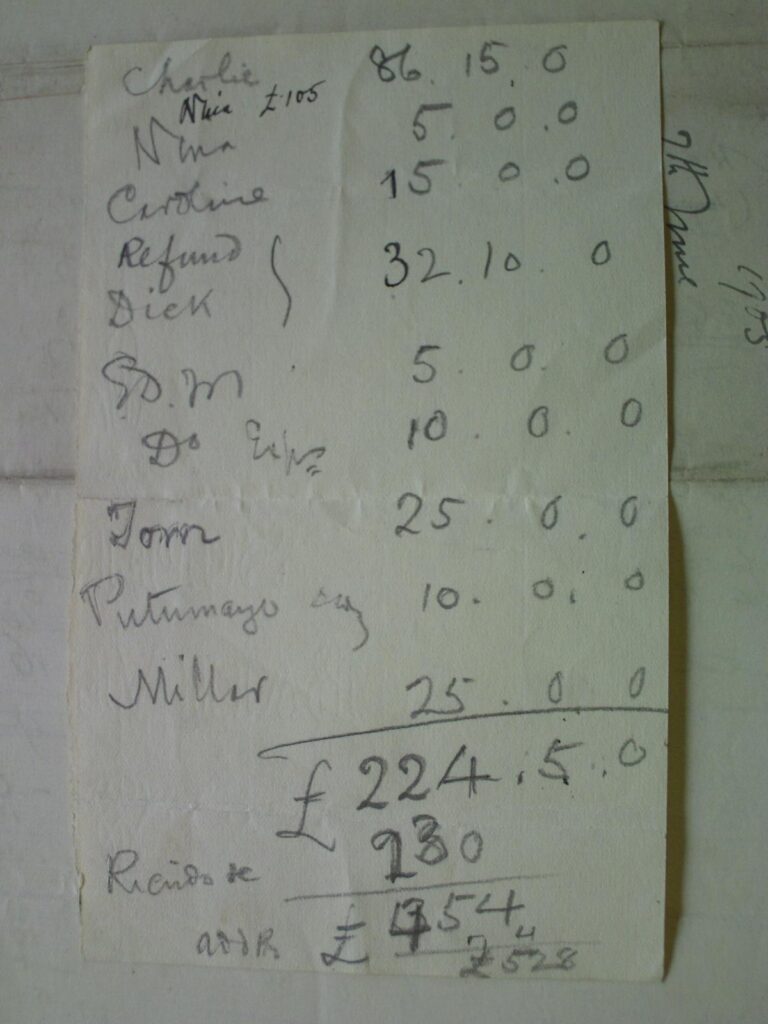

That ‘separate note’ is a single handwritten page in the National Library of Ireland (NLI) described as Rough Financial Notes by Roger Casement (MS 15,138/1/12). It is inscribed on both sides with records of outgoing payments. Many of the main undated payments record substantial amounts so that Millar’s £25 is not exceptional. The NLI file holds fourteen used cheque books and in many cheque stubs we find comparable payments; but there is no used cheque book for the May-July 1911 period. Casement certainly wrote cheques in that period but the used cheque book and dated stubs have disappeared. A stub with Corbally’s name would be conclusive evidence of the Corbally payment but there is no such stub and no used cheque book for that period.

None of the payments are recorded in the ledger nor do they seem to be in chronological order; the purpose was to sum up the amounts paid before leaving for South America in mid-August 1911. The figure of £105 is the cumulative total of 3x£35 quarterly payments to his sister Nina so its date is around end of June. It is clear that most if not all were made in June and July and one cheque to a Belfast friend is confirmed by a July 12 thank-you letter in the NLI file. The list was probably written in July and updated in August. On the reverse side payment totals are recorded for July and August. With regard to the Millar payment it is a fact that Millar had his 21st birthday on 23 June, 1911; however, the suggestion that the money was a birthday gift cannot be confirmed.

The ledger account and the NLI Millar note share several features which deserve attention. It might be coincidence that both refer to an identical sum of money – £25. And both refer to Millar – perhaps another coincidence. Then of course both involve Casement. And the ledger payment and the note are understood to be written around the same time – June-July 1911. Lastly, both payments seem to be gifts. If these are coincidences, we now have a chain of five coincidences. Simple coincidence is defined as the intriguing idea that two unexpected events did not happen by chance but share a hidden link or meaning. In this case we have five apparent coincidences in concurrence which strongly suggests the causal nexus which is missing from simple coincidence. While ordinary coincidences are infrequent, chains of coincidences are almost unknown. Indeed nothing other than a causal link can explain these apparent coincidences which are not due to inexplicable chance but are the result of human intention acting as sufficient cause. Coincidences do happen but they cannot be made to happen.

Explaining that causal link would expose how the ledger and the NLI note are related. If both were written by one person then the first written acted to bring about the other as cause produces effect. But they don’t record the same facts; the ledger records payment to Corbally while the NLI note records payment to Millar. It is necessary to determine which was written first.

If the ledger precedes the NLI note in time we must explain why the diarist recorded payment to Corbally but soon after contradicted that by recording the payment of an identical sum to Millar. If the ledger entry was written after the NLI note, the above contradiction is eliminated but a second contradiction appears with the references to Corbally and the motorcycle which are not present in the earlier NLI note and which contradict it. This fact clearly shows there is a double contradiction afflicting the documents regardless of which was written first. Either sequence produces contradiction which signals we have made a hidden assumption which is responsible for the contradictions. That prior assumption is that the two records were written by one person. As soon as we consider that the records were written by two persons, not by one, the contradictions are eliminated. Since the NLI note was indeed written by Casement it follows that the ledger entry was written by a second person, by someone other than Casement and is, therefore, a forgery. In short, Casement’s authentic record of payment to Millar is a de facto negation of the alleged payment to Corbally.

It was the most influential biographer Brian Inglis who in 1973 wrote “(and if one was forged, all of them were) …” – the common law principle falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus. Therefore it can now be stated with categorical certainty that all of the Black Diaries are forgeries and that this ultimately simple proof is irrefutable and conclusive. Two aspects add charm to this proof – its disarming simplicity and its debt to a crusader for authenticity without whom it might never have come to light. Let us give the devil his due and grant that it was the most ardent forgery denier, Jeffrey Dudgeon MBE who revealed the vital evidence that led to this proof and it was a most supreme irony that he did so by concealing that evidence too late.

*NLI MS 15,138/1/12

The payments listed are undated but cover the period before Casement left for the Putumayo in mid-August 1911. It is not known if the Millar payment was a gift or a loan. Conspicuously missing is any record of a payment to Corbally; also missing are the used cheque-book stubs recording the listed payments in the post April period although fourteen used cheque-books for before April are in the file. If as alleged in the ledger Casement had paid Corbally £25 on 3rd June, it must be explained why it is not recorded among these payments made in the same period.

These payments were made at various times from May to July but the nine main payments listed seem to have been written on a single occasion on or after 31st July. External evidence confirms the refund to Dick Morten was made in 2 parts, first on 28 April and second on 31st July. External evidence shows that two loans to Caroline were made by cheque in April and early July. The purpose of the exercise was not to record payments already noted on the cheque stubs but to calculate the total amount. Notes on the reverse confirm this. It cannot be determined if the recorded sequence of payments represents a chronological sequence because the corresponding cheque stubs are missing from the file. Certainly this file was examined by MI5, most probably by Frank Hall. The stubs would have verified the dates of the Millar payment and that of the alleged Corbally payment. The absence of a stub recording a Corbally payment would be sufficient and necessary motive for destruction of that used cheque-book. No other motive has credibility.

British Documents Prove Casement Forgery

The following is a two-part investigation of official documents held in the UK National Archives. These specific documents written by Home and Foreign Office officials are of crucial importance in the controversy about the diaries attributed to Roger Casement. Despite their importance, the extensive literature of the last sixty years has carefully avoided revealing their true significance. This article explains why.

Foreign Office confirms diaries forgery

In 1967 the British Government authorized the public release of once top-secret files to the Public Records Office. Among these were Foreign Office files relating to Casement in the period 1914 to 1916. Also in 1967 a new biography of Casement was commissioned from journalist-author Brian Inglis who was the first to access the secrets in those files. However, far from revealing those secrets in his 1973 book, Inglis ensured they would remain unknown to his readers. His book rapidly became the most influential study of Casement eventually producing a broad consensus that the former consul and humanitarian pioneer had been a disturbed pederast loner, an emotional fanatic traitor with a fractured personality. This portrait was copied verbatim by subsequent authors and Inglis went unchallenged for decades. Only in recent years has there been critical scrutiny of Inglis’ operation and that scrutiny has revealed the extent of his duplicity and sophistry.

Inglis contended the diaries were authentic but not from probative evidence; rather he created a portrait of Casement which made authenticity seem probable and credible. At the centre of this portrait we find the ambiguous figure of his manservant Christensen as a treacherous homosexual plotting to betray Casement to Findlay, Minister at the British legation in Christiania, Norway. It was Inglis who invented the allegation of Casement’s betrayal and it proved to be a potent propaganda weapon which was taken up by many later authors. Above all, it served to reinforce the defamation of Casement as pederast in the intensifying controversy about the diaries. To achieve this manipulation Inglis was constrained to suppress one of the secrets he had read in the released Foreign Office files. That secret was written in 1915 by Foreign Office official Arthur Nicolson who clearly confirmed that no betrayal took place or was contemplated.

The file in question is FO 95,776 and the narrative which emerges from its hundreds of pages reveals in convincing detail that no betrayal by Christensen took place and that, contrary to the allegation, Christensen successfully deceived Findlay for over two months with bogus letters, charts and fictions about Casement’s location and plans. Thus the magnitude of the false betrayal allegation is sufficient to discredit all Inglis’ supporting allegations and claims. Falsus in uno falsus in omnibus.

These documents were marked Private & Most Secret and they were written by British officials which signifies that their narrative constitutes an official account of events in those months. That account, kept secret until 1967, was contradicted by Inglis’ 1973 account which began with Christensen’s version of his encounter with legation secretary Lindley only to deny its veracity; “When the Foreign Office’s files on the subject were eventually opened for inspection, they told a different story.” Inglis’ ‘different story’ is a brief paraphrase of the top-secret memo invented by Findlay in October 1914 and sent at once to Foreign Secretary Grey. This shabby unconvincing document was also released in 1967 and it contains the first poisonous innuendo of homosexual scandal which Inglis cites. His paraphrase established the standard portrait of Christensen as a devious scoundrel who having ensnared Casement went voluntarily to the legation to sell him.

However, the official account was written in real time by the actual players Findlay and Nicolson and it is not credible that Inglis did not believe their account. Therefore, we must conclude he suppressed it in his book because he knew it was true and its truth compromised his plan to exploit the unknown Christensen as purported betrayer as the 1914 memo had insinuated.

Readers should note the following as symptomatic of the incoherence of the diaries controversy; at the same time that Inglis said nothing about the official account, US author B.L. Reid confirmed the official account and cited generously from FO 95,776 for his 1976 study.

Therefore the contents of that file testify not only to the falsity of Inglis’ version of events but also to all that derives from his version. What follows directly from Inglis’ version is the widely-believed claim that the diaries are authentic. It is important to note that Inglis contradicted the official account by replacing it with a paraphrase of Findlay’s invented memo. In the end it is the fact that no betrayal took place which is verified by FO 95,776 and it is this bare fact which demolishes all of Inglis’ subsequent claims for authenticity.

From late October 1914 until early January 1915 Findlay’s correspondence intensified with letters and telegrams almost daily to and from Nicolson in the FO; file FO 95,776 contains over fifty communications at this time which offer a detailed narrative of how Christensen systematically duped Findlay on Casement’s instructions.

TIMELINE

29 October: Findlay sent Lindley’s false memo to London. 30 October: Findlay met Christensen who on Casement’s instructions began the entrapment of Findlay. 28 November: Nicolson authorized the £5000 bribe. 3 January 1915: Findlay gave the handwritten bribe to Christensen. January 4: Nicolson advised nothing to be written, verbal only. January 6: Findlay apologized for written bribe. 13 January: Findlay apologized for the total failure of his coup against Casement. 14 January: Findlay sent a long typed letter to Nicolson apologizing again for his failure and errors. 14 January: a draft letter in FO 95766 reprimanded Findlay for his ‘great mistake’ in falling for ‘a ruse to get something from you in writing.’

A final most important fact is that on 5 January Christensen personally surrendered the bribe document to Meyer of the German Foreign Office thus definitively demonstrating the utter falsity of the Inglis betrayal claim.

This is what Nicolson wrote to Findlay on 14 January, 1915. “You will see that Christensen was playing a double game and that his reluctance to go on at the last was … merely a ruse to obtain something from you in writing. You made a great mistake in giving it … I have no doubt that Casement and his German friends will make the most of it.” What this confirms is that Christensen did not betray Casement and never intended to betray Casement. Expertise in hermeneutics is not required since no other interpretation is possible. It follows that the specific claim made by Inglis and repeated by Reid, Sawyer, Dudgeon, Ó Síocháin that Christensen betrayed Casement at the legation is categorically denied by the Foreign Office in the person of Arthur Nicolson CMG, KCIE, KCB, KCVO, GCVO, GCMG, GCB, Permanent Under Secretary for Foreign Affairs.

The deeper significance of Inglis’ duplicity is that the alleged betrayal of Casement slyly effects a fusion between treachery and sexual deviancy which infects and condemns both men as depraved politically, morally and sexually. The demonstrated falsity of the claim has serious repercussions for the dispute about the diaries. This is because the false claim of betrayal has conditioned the diaries dispute since 1973 and it constitutes the foundation stone of all authenticity accounts since published. All are dependent on this single deceit which effectively creates an illusory coherence in a subsequent pattern of interlocking deceits consisting of altered, forged and non-existent documents, selective framing, false attributions, omissions, circular reasoning, bogus logic and much innuendo. This elaborate web of duplicity is now without foundation and logically it follows that what it asserts is also without foundation.

Therefore the claim that the diaries are authentic cannot be sustained because it is founded on the demonstrated falsehood of an event which never happened. As it is false for Inglis so it is false for the other authors and likewise it is false for all claims that depend upon it as in a chain reaction. Therefore, it was the Foreign Office which guaranteed a priori the falsity of any future authenticity claims long before Inglis’ claim in 1973. Nicolson’s statement and Findlay’s apologies in FO 95,766 constitute a de facto proof of forgery.

Home Office proof of forgery

In October 1995 the British cabinet finally sanctioned the unrestricted release of the notorious diaries along with a large quantity of documents relating to Casement. Among these papers were extensive files compiled in 1958-59 when the Home Office was deliberating over the future of thediaries after the Home Secretary had come under increasing pressure from MPs and the press. At that point no-one outside government knew if the diaries even existed far less if they were genuine. Having refused all comment on the diaries for decades, the 1959 publication in Paris of the police typescripts finally forced the Home Secretary to instruct a Working Party to investigate, report and advise on a solution to the predicament.

The report of the Working Party of March 1959 contained a five-page ‘History of the Casement Diaries’ (PRO HO 144/23481). On page two we read “There is no record on the Home Office papers of the diaries or the copies having been shown to anyone outside the government service before Casement’s trial.” Although there is no official Home Office record, the typescripts were indeed shown to many influential non-government persons in the two months before the trial. They were also shown after the trial as confirmed by an official Note of the Working Party dated 7 May, 1958 which states “It was clear … that the diaries or copies of them, had been shown to a considerable number of people before Casement was executed. It would be difficult … to discover …the exact sequence of events in 1916 and who was responsible …”But while there are records of persons seeing the typescripts there are no records anywhere of anyone seeing manuscript diaries before or after the trial.

On the same page we also read “After the dismissal of the appeal a typescript copy was shown, on the Home Secretary’s instructions, to Mr. (later Sir John) Harris …” On that page and the next we read “Either copies or the diaries themselves were shown by Mr. (later Sir Basil) Thomson, Assistant Commissioner at Scotland Yard, to the American Ambassador, apparently at the Ambassador’s request. The Ambassador was given photographs of two passages from the typescripts.” Therefore in 1959 the Home Office did not know exactly what was shown to the Ambassador. Nonetheless, Thomson confirmed the showing in a letter to Blackwell, cabinet legal advisor, who described ‘the diary’ as “ … many pages of closely typed matter.”

Theobald Mathew, Director of Public Prosecutions, also confirmed “there is no written record of what use was made of the copy extracts from the diaries …” In a letter dated March 9 we read “ … it was taken for granted in 1916 that the diaries were genuine …” Clutterbuck, Ambassador to Dublin, admitted his uncertainty about when the police found Casement’s luggage and accepted the possibility of its seizure long before Casement’s arrest. “The story of the diaries as revealed in the Home Office papers does not provide conclusive evidence that no forgery took place.”

What this signifies is that in 1959 the British government did not possess a single document which gave the name of any independent person who had seen manuscript diaries in 1916. But it did possess the names of several independent persons who had seen the police typescripts in 1916. Moreover, in 1959 it did not possess any of the photographs of the typescripts which were made and did not possess any of the photos allegedly made of manuscript diaries in 1916. In short, the Home Office in 1959 did not possess anything which would testify beyond all doubt to the material existence of manuscript diaries in 1916.

What is revealed in the Working Party papers is that the four civil servants were handicapped by an irrational cognitive model which compelled them to believe the diaries were self-evidently authentic which conveniently made empirical evidence unnecessary since there was none. This hostile cognitive trap led them to announce “…the diaries speak for themselves and are likely to convince all but fanatics of their genuineness.” They were aware of persistent claims of forgery both in Ireland and elsewhere but a kind of ‘patriotic faith’ sustained them against those they called “nationalist fanatics”.

To these facts we must add the following; the various biographies attesting to authenticity – by MacColl, Inglis, Sawyer, Dudgeon, Ó Síocháin, Philipps – some of these do give the names of independent persons who allegedly saw manuscript diaries in 1916. But in all these cases official documents confirm that only police typescripts were shown to the alleged witnesses. Sawyer, Dudgeon and Ó Síocháin falsely claim that Baptist missionary John Harris was shown manuscript diaries and the books by Dudgeon and Ó Síocháin ignore HO 144/23481 which was available to them at Kew. Philipps too falsely claims that Harris was shown “the photographs of the extracts” while he ignores the fact verified by HO 144/23481 that the photos shown to the US ambassador were photos of typescripts. Certainly photographs were made but none have survived; the destruction of official evidence betrays the evidence is false. Philipps ‘solves’ the problem by simply ignoring the existence of the police typescripts thus obliging his readers to assume manuscript diaries were shown; even so, Philipps fails to verify a single showing. Reid proves unable or unwilling to distinguish between the typescripts and manuscripts by referring vaguely to ‘diary materials’. Despite his claim on page 418 that “Apparently anyone of influence could have a look.” at the diaries, he is unable to name anyone who did ‘have a look’.

In conclusion, of these six authors whose research covers a seventy-year period with 3,400 pages, not one of them can state the name of a single independent witness who saw manuscript diaries in 1916. Taken together, the above verified official facts constitute sufficient grounds for asserting that today’s manuscript diaries were not shown to anyone in 1916 because they did not exist. From this it follows that PRO HO 144/23481 provides a de facto proof of forgery.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply

Fabricating the 1910 Diary

Information recorded in his 1910 notebook and known only to Casement remained secret until 1914 when the notebook was found by British intelligence who subsequently exploited its potential as testimony to ‘authenticate’ the invented 1910 ‘black diary’.

In the National Library of Ireland there is a long, handwritten document which is the undisputed work of Casement. This is a detailed account of his day-to-day investigation into the Putumayo atrocities in the latter months of 1910. Today this document is called The Amazon Journal. In the UK National Archives there is a handwritten desk diary attributed to Casement, most of which is a partial account of the same period and which contains around 22 references that allude to homosexuality. This is named the Dollard diary after the Dublin stationery firm.

The precise relationship between these two documents has never been fully determined and even where it is proposed that both are Casement’s work, it remains to be demonstrated which was written first. This is necessary because those who hold that both are Casement’s work insist the Dollard was written first and that The Amazon Journal is a later version. The Amazon Journal consists of 128 handwritten, double-sided foolscap pages containing around 143,000 words and it is 10.22 times longer than the entries for the same period in the Dollard diary; it contains no compromising writings whatsoever. Its existence has caused difficulties for those who believe that the Dollard diary was written by Casement, not least because the principal reason for believing Casement wrote the Dollard is a resemblance in the handwriting. Whereas there is evidence that Casement wrote The Amazon Journal in 1910, there is no evidence to show that it was written after the Dollard. To ease those difficulties, it has been suggested that both diaries are genuine and that The Amazon Journal is a cleaned-up version of the Dollard. Therefore it is the inclusion in the Dollard of the contentious references that provides the only rationale for its existence. This, however, does not explain why anyone would write some 14,000 words merely to conserve 516 words of nonsense.

In the introduction to his 1997 book Roger Casement’s diaries: the black and the white, Roger Sawyer claims that the Dollard diary was written by Casement when in Peru in 1910; it was his original diary complete with compromising entries. At the same time Casement was also composing the much longer Amazon Journal and drawing upon the Dollard as source material or as an aide-mémoire. According to Sawyer, The Amazon Journal was intended as preliminary material for a book. This explains why it contains no compromising references; ‘evidently it was written in the hope that it would eventually form the basis of a published work and … it had the initial value of being a useful aide-mémoire for the official report … ; as he writes a fuller, official, version eventually intended to form the basis of a published work.’

Sawyer is rightly concerned with sequence because the first written seems to have a strong claim to authenticity. It is counter intuitive to compose a false document first and then compose an authentic document ten times longer expanding on most of the events in the false document. The supposed later Amazon Journal seems to share its undisputed authenticity with the supposed earlier document. Sawyer does not contest Casement’s authorship of the Journal but he does not explain why two diaries were supposedly written by one person to record the same period of time save to suggest that the diarist intended to record erotic experience in the Dollard. Yet this is unconvincing because only 3.6% of that diary might be described as alluding to erotic matters. It will therefore be necessary to expose how Sawyer deploys specious reasoning and manipulated chicanery but will reveal precisely how and when the Dollard diary with its fake erotic evidence was manufactured.

Sawyer’s book refers to entries in the Dollard diary as follows: ‘On three occasions in the Black Diary, the author seems to be alluding to the White Diary (4, 21, 29 October), and on the blotter facing 6-8 October he actually quotes from it.’ While it is true that these allusions to the Amazon Journal do appear in the Dollard, it is misleading to claim the blotter text quotes from The Amazon Journal; only two words of 79 on the Dollard blotter appear in The Amazon Journal. In fact Casement left a blank space in the Journal where that text was intended. That blank space is intentionally omitted in Sawyer’s published version of The Amazon Journal (which he also calls the White Diary). Indeed Sawyer’s entire Amazon Journal entry for 8 th October does not correspond to the version published by Angus Mitchell which is considered authoritative. The motive for that omission will soon become clear since it is consistent with Sawyer’s manipulation of the original sequence of events recorded in his published version of The Amazon Journal entry for 8th October.

Here is the text on the Dollard blotter which Sawyer counts as of great importance:

‘On 8th Oct at Ultimo Retiro. Measurements of one man & a woman. The man’s name Waiteka, ‘the fearless skeleton’ of my Diary, who denounced the ‘cepo’ Age about 35-40. Weight, say 120lbs. Height 5’6’’. Chest 35’’. Thigh 17’’. Calf 11 ¼ ‘’ – (his ankle in cepo just fitted.) Biceps 9 ½ ‘’ Forearm 8’’ Stomach 32’’.

Woman Theorana by name. Age say 22 yrs. Weight 104. Height 4’7’’. Chest below breasts 31’’. Stomach 33’’. Thigh 19 ¾ ’’. Calf 12 ¼’’ . Biceps 9 ½ ’’. Forearm 8’’.’

The ‘cepo’ is the wooden punishment stocks used to torture and kill the native slave gatherers of rubber. Since the details cited above seem authentic their provenance must be established. In The Amazon Journal, however, these details are not present and there is merely the phrase ‘I was smiling with pleasure that this fearless skeleton had found tongue …’ That the phrase ‘’the fearless skeleton’ of my Diary’ appears in the Dollard confirms that the diarist has seen The Amazon Journal but that fact does not identify the diarist who Sawyer alleges is Casement. The source of the detailed measurements in the Dollard is certainly Casement which fact appears to identify Casement as author not only of those measurements but also of the entire Dollard diary. That impression remains intact until the true source of the details is revealed which will expose the Dollard diary as another example of manufactured evidence.

Sawyer at once runs into contradiction. He claims that the Dollard entry for 8th October was written before the same-date entry in The Amazon Journal yet he asserts that the Dollard diarist found the fearless skeleton reference in the 8th October entry of The Amazon Journal. But that entry, according to his thesis, had yet to be written. In fact this contradiction of which Sawyer is quite unaware establishes definitively that The Amazon Journal was written before the Dollard. It entirely escapes Sawyer that ‘the fearless skeleton’ phrase in the Dollard could just as logically have been lifted from the already-written Amazon Journal. In addition, the Dollard diarist blunders again by citing the name ‘Waiteka’ which does not appear in The Amazon Journal entry. Indeed that name comes from a source known the diarist and to Sawyer and concealed by both. It is the reference to ‘my diary’ that betrays the 8th October Dollard entry as an embedded authenticating device. Close scrutiny demonstrates that it fails. The Dollard entry derives an illusory authenticity from the authentic Amazon Journal by identifying the source of the words ‘fearless skeleton’ in The Amazon Journal. The parasitical mechanism creates a deceptive correspondence between statements in both documents so that the authenticity of the statement in one document passes imperceptibly into the statement in another document. But the repetition of the same words in the second document does not demonstrate that one person wrote those words in both documents.

The Amazon Journal consists of loose foolscap sheets which require a stable support hence only written when circumstances permitted and mostly indoors at night. Thus his Amazon Journal account of events at the stocks was written some time after his investigation earlier that day in the company of commission members. The physical measurements taken at the stocks were certainly noted in writing at once since such detail could not be recalled by memory later. It is confirmed that Casement used notebooks when outdoors as he was on this day inspecting the stocks. That he intended to insert these details later in The Amazon Journal is demonstrated by the incomplete locution in The Amazon Journal entry – ‘Here are it’s measurements … His name was …’ Conspicuously, Sawyer does not publish this locution in his manipulated version of the White Diary entry for 8th October.

When the Dollard diarist refers to ‘the fearless skeleton of my Diary’ he is confirming that The Amazon Journal entry of 8th October precedes the Dollard entry written on the blotter for 8th October. It is not clear when Casement wrote that 8th October Amazon Journal entry but at the earliest it would have been late on the 8th . It follows that the Dollard diarist wrote ‘’the fearless skeleton’ of my Diary’ after 8th October. The fact that Casement did not include the measurements of the ‘fearless skeleton’ in The Amazon Journal can be explained by the information being already recorded in situ in the green notebook referred to in both The Amazon Journal and the Dollard diary.

Confirmation of Casement’s use of notebooks when on the move is found in the Casement-Roberts Correspondence at Rhodes House. Brit. Emp. S22. When responding to MP Charles Roberts on 27th January, 1913 Casement referred to The Amazon Journal as follows; “…I have not read it for two and a half years!… Also I have two notebooks in which are other portions of the diary and sometimes letters are to go in when I have left blanks…. The mass of writing I had to do…generally carried me far into the night. … you have the diary … If you get it well typed I can fill up from my other notebooks any discrepancies or omissions.” That correspondence also confirms that Roberts made two typed copies of The Amazon Journal he received from Casement and in June, 1913 one of these was given to Casement along with the original. Thus the manuscript plus the typed copy plus the notebooks were in Casement’s possession in mid 1913 and would later have been stored in his luggage either at Ebury Street or at Allison’s warehouse.

It is now widely accepted that Casement’s luggage was seized in late 1914 by either police orintelligence officers. Sawyer himself and many other forgery deniers have long accepted that the luggage was in police possession long before the 1916 arrest; Dudgeon seems to be the only exception. Therefore intelligence officers were able in 1914 to examine both the manuscript and typescript Amazon Journal plus the notebooks. The names and physical measurements in the notebook would have made little sense until cross checked with either version of the Amazon Journal in their possession and the full context understood. The intelligence officers would note the ‘fearless skeleton’ sentence in the Journal and would see that the names and measurements from the notebook had not been entered in the blank space reserved for them in the Journal. This was an unexpected prize; they had found genuine information in late 1914 from a unique source known only to them and which would remain known only to them. Those details from the notebook would eventually appear in the 1916 Dollard typescript and later in the manuscript ‘black diary’ where they would ‘authenticate’ both. Obviously none of Casement’s notebooks have survived; a great deal of ‘tell-tale’ Casement material was destroyed soon after the execution.

Like the other ‘black diaries’, the Dollard is now demonstrated to be a definitively proven forgery. Sawyer’s consistent dishonesty over several decades was masked by a veneer of old-world courtesy performed with self-effacing modesty to deceive the unwary. However, where Sawyer went wrong was that his determination to deceive readers made him overlook the fact that copying a Shakespeare quotation into one’s diary does not demonstrate that Shakespeare wrote the diary.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply

A Fatal Diagnosis

Close analysis of errors and chronological anomalies in the diaries shows they are symptoms of a deadly viral infection; the diaries are retrospective fictions of real-time immediacy.

Page 27 of the 1911 typescript (see below) contains a concentration of errors and anomalies of many kinds which merit examination as symptoms of a malady. There are about ten spelling errors which include the names of Casement’s colleague (twice) and also of two personal friends. Four times the names of well-known river vessels are mispelt and a word given in Spanish is on the following line given in Italian. There are also many typographical errors. When compared to the manuscript diary it is clear that the typescript is not a faithful copy. There are several words misplaced and, strangely, one word appears on the typescript but not in the manuscript. An ampersand & in the manuscript becomes ‘and’ in the typescript. ‘Finally’ in the typescript is ‘ferociously’ in the manuscript. An error in the first entry for Tuesday defies explanation. Having anticipated arrival in Pará “…before 6p.m. tomorrow evening …” thus indicating arrival on Wednesday evening, the diarist after two lines announces “Arr. Para 5.40 anchored …” The following entry for Wednesday morning confirms the diarist “got ashore just 15 housr [sic] after we arrived.” That seems to confirm the vessel arrived on Tuesday evening some 24 hours before anticipated arrival time. To add to the confusion we find in the manuscript a short bent line inserted at the end of the Tuesday entry which is perhaps intended to link the last words to the Wednesday entry below. But this line does not appear on the typescript.

However, this brief summary does not exhaust the confusion on page 27. The Wednesday entry is the longest by far and it purports to relate the diarist’s activity from early Wednesday morning to 1 am on Thursday morning, a time span of eighteen hours mostly devoted to homosexual matters in Pará. It is when we move to the following entry for Thursday that we receive a shock. This opens “See Yedy’s entry, in error made under Wednesday. I only landed to-day at 8. 30a.m.” In the manuscript diary the first sentence becomes “See yesterday’s entry, in error under Wednesday.” Obviously the typescript does not correspond exactly to the manuscript.

It is probably wise at this point to inform readers that external evidence proves that the Wednesday entry is entirely false. On Wednesday Casement spent the whole day travelling on the river steamer S.S. Hubert and he went ashore in Pará at some time on Thursday as confirmed by the local newspaper Folha do Norte in its Friday ‘Mares e Rios’ column. It will also be demonstrated that the remedial Thursday entry is as false as the Wednesday account.

The Wednesday account is far from being a simple slip by the diarist who has by mistake on Thursday written his account of Thursday in the blank Wednesday space. He has not explained why on Thursday the Wednesday space was blank. Nor has he explained the confusion of the arrival time in the Tuesday entry.

It is important to note that page 27 contains no less than nineteen references to specific clock times such as 9 a.m., 6pm etc which create an impression of real-time precision. One of these times is of great significance – the ‘home at 1. a.m.’ cited at the end of the Wednesday entry which when ‘corrected’ by the short Thursday entry refers to 1 am on Friday morning. It follows that the short entry in the Thursday space was not written on Thursday but at some time after Friday 1 am. Therefore the Thursday entry is false and it follows that what it asserts regarding the Wednesday entry is also false. Investigating this double falsehood will reveal the hidden virus which will prove fatal for the status of the diary.

The entries on page 27 are predicated on an impression of real-time immediacy, the events being apparently recorded as they happen but the double falsehood demonstrates this is an illusion. The events in the Wednesday space did not happen on either Wednesday or Thursday or at any other time. The real-time illusion is undermined by the opening words of the Thursday entry which refer to “Yedy” and “today”, both specific day identifiers. The Wednesday entry identified in the Thursday entry as “Yedy’s” is contradicted by the ‘correcting’ claim in the Thursday space which implies that the Wednesday entry was written “today”, Thursday. The entry in the Wednesday space should have been referred to as ‘the above entry’. Use of the word “yesterday” is a misjudged attempt to maintain the illusion of real-time immediacy but it compromises control over the chronology of the narrative. The diarist chose that word because it appears to ‘anchor’ in real time the imaginary events placed in the Wednesday space. Real time means ‘in the same time frame’. Retrospective means ‘at a later unspecified time frame’. Here we have two clear examples of retrospective diary entries which fact undermines all other entries and thus compels us to consider that the entire diary is retrospective.

In order to discover what has gone wrong on page 27 we can examine other confusions in the diaries. Possibly the most significant is found in the 1910 Dollard diary where the error is almost identical to the one under examination. This concerns the lunar rainbow episode which in the Black Diary is falsely reported on 7th November. In Casement’s Amazon Journal the sighting of this phenomenon is clearly dated 6th November. And the attempted corrections are almost identical since they rely on retrospective reshuffling of the sequence of events. The 7th November erroneous entry is overwritten in blue crayon with “This is on Sunday Night”. The following entry of 8th November is crossed out after a few lines to be followed by a new entry for that same date with the ‘explanation’ “Made a mistake of a day since Saturday!” The incoherence here is so similar to that on page 27 that it is reasonable to look for a common explanation.

Again the typescript does not correspond to the manuscript version. The scored-out entry for 8th is not in the typescript and the ‘explanation’ “Made a mistake …” is missing. The main 7th entry manuscript overwritten “This is on Sunday Night” does not appear on the typescript.

Obviously the 7th November entry is entirely false in the double sense that the lunar rainbow did not occur on that day and that the remark “This is on Sunday Night” was not overwritten on 7th but is retrospective – written after that date.

Here is a list of these errors in both diaries;

1 – November 7, 1910 – false entry overwritten retrospectively – “This is Sunday Night.”

2 – November 8, 1910 – first entry retrospectively scored out.

3 – November 8, 1910 – new entry added retrospectively including “Made a mistake of a day since Saturday!”

4 – December 19, 1911 – wrong arrival time and remedy line added retrospectively.

5 – December 20, 1911 – entry entirely false. No events recorded on that date.

6 – December 21, 1911 – correction for previous entry added retrospectively after December 21.

The above instances amount to six related proofs of forgery all of which rely on retrospective alteration of diary entries. It is time to explore the causes and meaning of this retrospective dimension. The alterations are of necessity retrospective attempts to regain control of the narrative. In particular it is the risk to real-time coherence which makes the repairs necessary.

However, these diaries purport to be not only personal documents but also to be top-secret private records of extensive criminal behaviour; they are not therefore documents to be shared with others. Confusion in the narrative would be perceived by external readers but to a private author/diarist should be of no concern because, knowing what he has just experienced, it would not appear to him as confusion and, even if noticed, would be of no significance. In short, it is the presence of these retrospective repairs which indicates the diarist is composing the diary in the knowledge it will be read by others. It is therefore not a private diary at all.

The Wednesday entry contains incriminating behaviour which is consistent with similar behaviour in so many other entries as to indicate that recording such events was the purpose of the diary. To openly delete or cancel that entry was not an option since doing so would leave evidence that the incriminating behaviour did not happen and was therefore invented. Thus it would undermine the purported authenticity of all the incriminating texts throughout the diaries.

In fact these observations are supported by the ‘voice’ which articulates the retrospective repairs. The self-correcting voice of the Thursday entry on page 27 is not the voice of a genuine diarist in real time but is the voice of an author revising and repairing. It is a ventriloquist’s fake voice speaking through an invented diary. A genuine diarist writing daily would not misplace an entire day’s events then correct the error by referring to a previous entry. The cross reference has the quality of an editorial correction not of a spontaneous diary note. It is this retrospective reshuffling of the sequence of events which exposes them as fictitious. This is not the behaviour of a diarist writing in real time. It is the behaviour of an author editing a fake account which he purports is his own past.

The combination of misdating, retroactive redistribution of events and cross referencing of one day’s entry against another reveals that the diary was not written on the days it purports to cover. Rather it was composed later with the diarist trying to project immediacy but betraying the artifice by mistakes in chronology. Those mistakes were caused by tensions between two time frames of reference. The first time frame was that of the invented real-time diary narrative while the second was the natural real time lived by the anonymous diarist. Composition of the narrative demanded constant control of the first and suppression of the second which resulted in tensions because the time frames are ontologically and psychologically incompatible.

If one entry is retrospective, all entries must be deemed retrospective as if infected by the same virus. This is because the individual entries are closely related like members of a family; they are presented in a day-by-day sequence and represent a connected chronological narrative purporting to be an account of the real-time experience of the diarist. When the real-time consistency is breached by a demonstrably false entry which indicates it was written later than the diary date attributed to it, it follows that nothing can confirm the other entries in the connected narrative are in real time. Therefore the 1911 diary can be described as a retrospective fiction of real-time immediacy composed by an unknown diarist. This description can also be applied to the 1910 diary.

In 1973 Casement’s most influential biographer Brian Inglis wrote of the diaries that “… a single mistake in any of them would have destroyed the whole ugly enterprise.” A single mistake? In only two diary pages we have explored six mistakes which yield six proofs of forgery. And there are many more mistakes.

0 Comments