Casement – Invisible Evidence

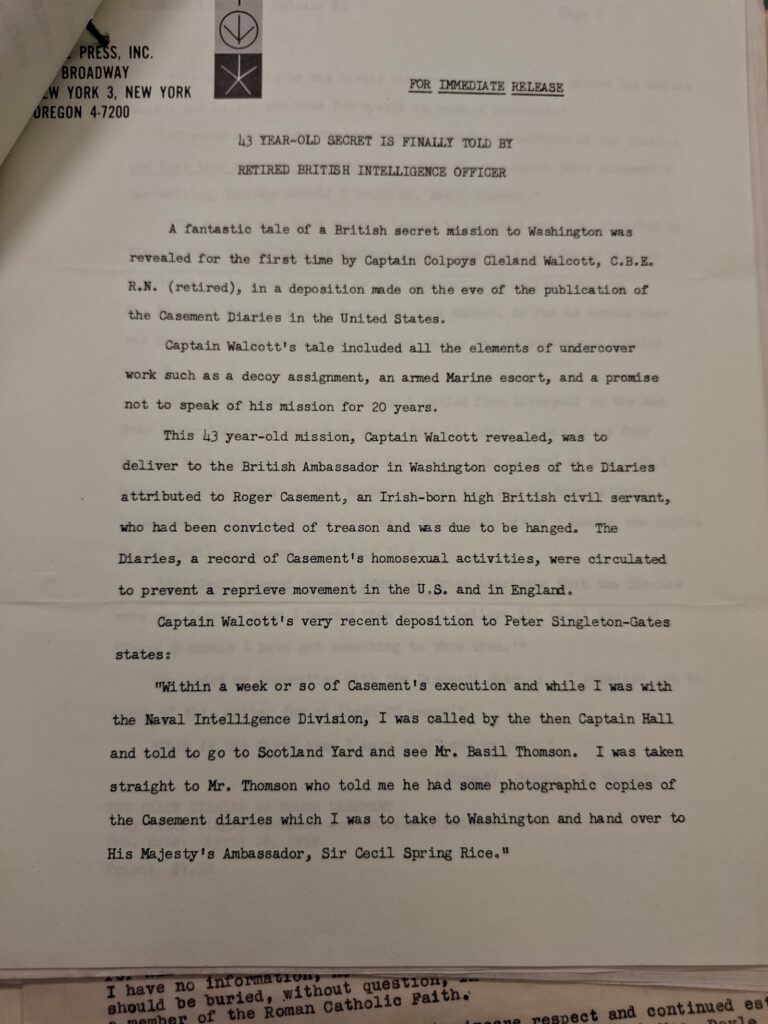

The controversy over Casement’s life and death reached a critical point in 1959 with the publication of obscene diaries attributed to him. The no-comment policy was abandoned and selected persons were given access to the documents. With publication of the ‘Black Diaries’ a press release revealed a top secret mission by British Intelligence in 1916.

§

The name of Peter Singleton-Gates has long been linked to the confused legends about the diaries attributed to Roger Casement. He was a young Fleet Street reporter and was probably also a police informer. He certainly knew CID chief Basil Thomson who in May 1922 six months after being dismissed from the Metropolitan Police, secretly delivered to Singleton-Gates’ home a bundle of typescripts which he had stolen from Scotland Yard. Singleton-Gates agreed never to reveal Thomson’s identity and followed his suggestion about using the materials for a book. In 1925 when his agent was unable to find a publisher, a contact in the Evening Herald published a promotional announcement for his book. At once the Home Office threatened prosecution and his home was searched. It was only in 1959 that he finally managed to publish the book in Paris and New York. In the intervening 34 years however, it seems probable that he was collaborating with British intelligence to discreetly authenticate the typescripts since he claimed he was shown handwritten diaries. He also sold photographic copies of the typescripts. In a 1956 Spectator article he stated that he had never doubted the diaries were authentic.

Basil Thomson died in 1939 but for unknown reasons Singleton-Gates did not feel that death dissolved his verbal promise. The bond was therefore stronger than that of a solemn marriage vow and as if to confirm this, Singleton-Gates stated that not even his wife knew his secret. His fascination with Casement lasted until his own death in his 80s. Thomson’s need for anonymity is understandable; but it is unclear why Singleton-Gates kept a promise to a dead man for several decades unless Thomson’s name was not the only secret to be protected. Singleton-Gates remains an enigmatic figure whose motives are suspect. Attempts to trace his journalistic career, to locate his articles, even to identify his newspaper (probably The Evening Standard) are vain. There are reports he was involved in fraudulent schemes such as the conspiracies over Kitchener’s death. Reviewing his book in The New York Times on 26 April 1959 Irish academic Roger McHugh wrote, ‘… last month a London reporter quoted Mr. Singleton-Gates as admitting that he had faked several news stories in the past; the most spectacular was in 1921 when, posing as “Lieutenant-Colonel Singleton,” he claimed to have found the body of Lord Kitchener, lost at sea five years previously. “Kitchener was still hot news,” he told the reporter, “and we cashed in on him” (Sunday Express, March 1). It seems unlikely that this fraud, which involved the Home Office and Scotland Yard, endeared Mr. Singleton-Gates to those in authority in 1922.’

For the US promotion of his Casement book in 1959 Singleton-Gates issued a press release containing details more suited to a spy thriller, a le Carré intrigue. The essential details are true. But the narrative is a masterpiece of journalistic ventriloquism. The original texts below were donated to The National Archives of Ireland by Francis Doyle, the US attorney at Casement’s trial.

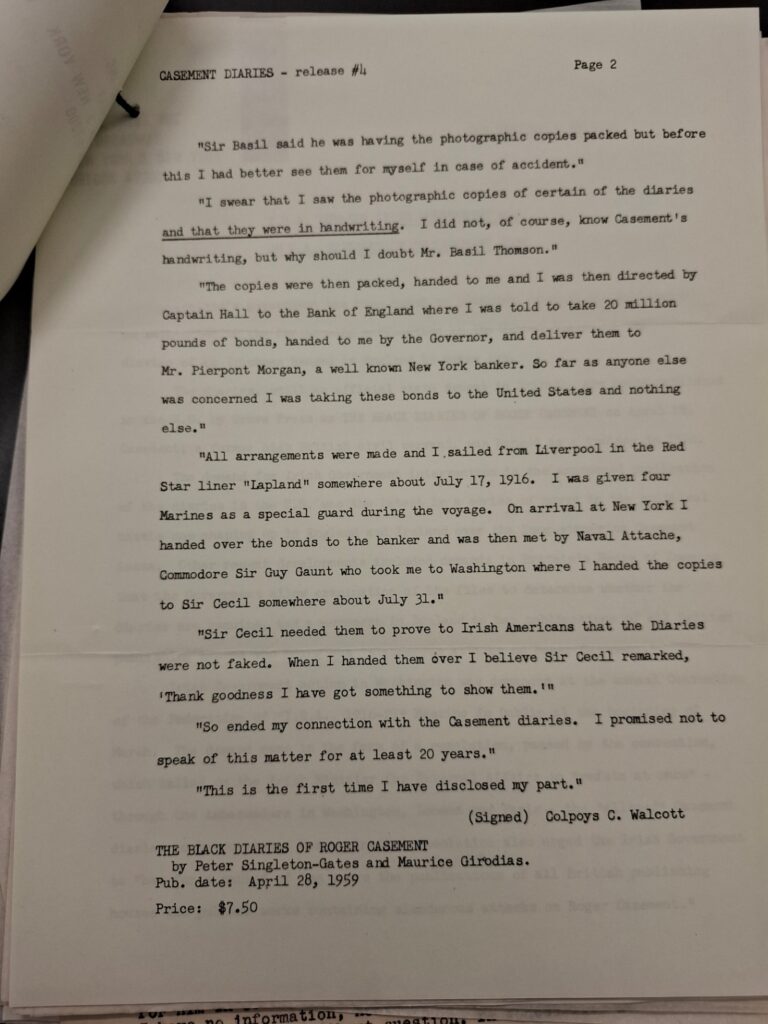

That Singleton-Gates composed the deposition and not Walcott is verified by Singleton-Gates himself in his 1966 typescript held in NLI. At best the deposition in the press release is a shorter reworked version of Walcott’s original account which was posted to Singleton-Gates. None of Walcott’s sentences are reproduced by Singleton-Gates and there is nothing to confirm that 81 year-old Walcott ever saw or signed the press release deposition. The most sensitive part is the two paragraphs on page 2 referring to the photos being shown. The narrative is framed to divert attention from the fact that Walcott’s account admits he did not see any diaries. His account reads ‘I never read the diaries but I was careful to make sure that the copies were photos of the original … Thomson said there was a lot of doubt being cast on them.’ But Walcott does not explain either how he verified the photos or that he examined any original diaries which was the only means of verification. This was a predicament Singleton-Gates had to resolve. Referring to the fact that Walcott saw the photographs just before they were packed, Singleton-Gates attributes a meaningless locution to Walcott which does not appear in his original account; “… I had better see them for myself in case of accident.” He is referring to the photos. What can this mean? Does it mean that Walcott’s looking at the photos might prevent a later accident to either him or the photos? Does it mean the photos, easily re-printable from the negatives, are more valuable than the 20 million sterling bonds? It is an explanation which explains nothing.

The following sentence attributed to Walcott in the deposition was invented by Singleton-Gates; ‘why should I doubt Mr Basil Thomson’. This does not appear in Walcott’s account reproduced in Singleton-Gates’ NLI typescript. This clumsy invention betrays what Singleton-Gates wanted to conceal – that no diaries were shown to Walcott. Decoded it reads; Thomson gave his word that the photos were copies of unseen diaries and that word is truth.

The second paragraph starts on the defensive; “I swear that I saw the photographic copies …” of diaries he had never seen. Singleton-Gates is on the defensive here because by 1959 he could not allow any doubt about authenticity to seep out on the eve of finally publishing his book after 34 years. To compensate for Walcott not seeing any diaries, Singleton-Gates deploys the carefully underlined decoy phrase “… and that they were in handwriting.” This invented phrase which is not in his original account, allows Singleton-Gates to ventriloquize Walcott’s voice to authenticate the photos as copies of invisible diaries. And to confirm this chicanery, he again resorts to ventriloquism to have Walcott confirm Thomson’s integrity with “… but why should I doubt Mr. Basil Thomson.” Why indeed doubt the man who published four conflicting versions of the diaries’ provenance, the man who perjured himself in 1926 when convicted for public indecency in Hyde Park?

From Scotland Yard Walcott went to see Walter Cunliffe, Governor of the Bank of England, as instructed by his chief, Blinker Hall. According to the press release the transport of 20 million sterling bonds was a cover for moving the top secret photographs to New York, photographs which had no monetary value and which have never been seen since 1916. There is no explanation why any cover was required and no explanation why the photos were not sent as normal by diplomatic bag. The melodramatic mystery aspects in the press release are intended to conceal the fact that no diaries were shown to Walcott. Thus Singleton-Gates took a risk in relating Walcott’s story. Since Walcott was not allowed sight of original diaries in 1916, it follows that no diaries were shown to other intelligence officers at that time and that Singleton-Gates was aware of this. He composed the press release after realizing that despite being with Thomson in his Scotland Yard office Walcott never saw any diaries. Singleton-Gates knew the press release was a de facto proof that there were no original manuscript diaries in 1916. This awareness motivated his decision to underline the phrase referring to handwriting which he hoped would allay any doubts.

Singleton-Gates made a serious error in the deposition where he has Walcott swear not only to seeing photos of handwriting which he could not identify but in the same sentence he also has him swear he identified the photos as images of ‘certain of the diaries’ which he had never seen. This sentence is not in Walcott’s account. Singleton-Gates hoped that his emphatic underlining of one phrase would conceal or neutralize the contradiction.

Walcott’s locution ‘… why should I doubt Mr. Basil Thomson’ is the fallacious argument from authority (argumentum ad verecundiam) which says Thomson’s word was above suspicion and could not be tested without disrespect. It proves conclusively no diaries were seen from which it follows that the photos were not evidence of diaries by virtue of the origin and primary meaning of the word evidence – videre: to see.

It is a fact that the photos Walcott delivered to Washington have never been seen since and it is safe to infer they were destroyed. Destruction of such evidence by those who produced the evidence is an unequivocal proof that the evidence was false. Although the press release was published 66 years ago no other Casement author has ever referred to it. Leading forgery deniers Ó Síocháin and Dudgeon say nothing in their lengthy studies which fact is best explained by their tacit recognition that it constitutes a de facto proof that no diaries existed in 1916.

Singleton-Gates’ 1966 typescript called Casement: A Summing-Up is held in NLI. It too was unpublished, either banned on grounds of political sensitivity following the 1965 repatriation of Casement’s remains, the state funeral and the secret offer of the diaries to Dublin or deemed unreadable on account of its turgid, pompous prose. But what it does not contain is what matters most in resolving the long controversy. In its 240 pages it does not contain the name of a single independent witness testifying to having seen manuscript diaries in 1916. But this is no surprise since decades of later research by authors both for and against authenticity has equally failed to name a single witness. It is this fact which utterly devastates the claim of authenticity.

0 Comments